Conservation of Resurrection of Antioch Mosaics in Turkey

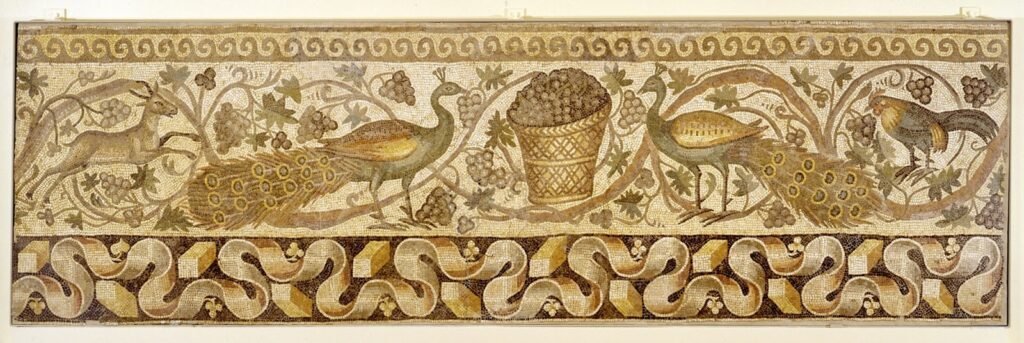

The BMA’s Antioch mosaics like the "Bird Rinceau" and the “Striding Lion” feature fish, a lion, gazelles and birds, including peacocks.

The Bird Rinceau Mosaic

This blog focuses on the bird theme and particularly the latter fowl, and looks at how the geopolitics of the region allowed this exotic bird to become depicted in the art of Antioch. My earlier blog traced the arrival of Alexander the Great in the early geopolitics of what became Antioch. Upon his death, his empire was carved up and the largest piece included Syria and Mesopotamia. Antioch was built as the new capital in what was then the Seleucid Empire. Eventually Antioch became part of the Roman Republic and then the Roman Empire.

Scholar P. Thankappan Nair notes that many credit Alexander the Great for “spreading the cult of the peacock from India to the West[1]” when he conquered the lands from Greece to India. Yet, because the peacock was one of the sacred animals of Hera, the Greeks already held the bird in high regard.

Christianity came into existence during the Roman Empire. As it spread and started to appeal to non-Jews, early Christians understood they need to appropriate pagan practices and symbols to make it easier for non-Jews to understand. Often, Christians assigned a new meaning to the symbols. Eventually, Christians appropriated the peacock from Greco-Roman pagans and remade it into a symbol of Jesus’ resurrection. There was a well-known legend at the time that the flesh of a peacock could not decay, which probably supported the Christian resurrection story. Also, Roman coins at the time frequently depicted the image of a peacock, too. The Romans used the bird to symbolize a princess becoming a god after she died. This, too, supported the Christian resurrection story. Christians used the peacock symbol of the resurrection to decorate their tombs, adopting it from the Romans who originally used pictures of peacocks to decorate their tombs and funerary monuments.

On the info plaque, the BMA says that the mosaic is from a Christian household because of the crosses on the border and the inclusion of peacocks. As this blog illustrates, the history of the peacock is more complicated than that.

While I was working on this concept for the past few weeks, I was pleasantly surprised today to see a possible new example of Antioch’s use of peacocks in a mosaic in the Museum Hotel Antakya, in Turkey, where Antioch is today (no longer in the province of Syria as it was during the Roman Empire). When construction began on what was proposed as a 400-room luxury hotel, they discovered artifacts from Antioch and decided to incorporate them into the hotel. As a result, according to the Smithsonian, the hotel hovers over the “world’s largest single-piece floor mosaic (more than 11,000 square feet) and the first intact marble statue of the Greek god Eros. All told, the researchers unearthed 35,000 artifacts representing 13 civilizations dating back to the third century B.C.[2]” Below is a picture of one of the fabulous mosaics that was preserved, which looks similar to the Antioch mosaics at the BMA.

Another spectacular mosaic at the hotel is replete with birds, including chickens, guinea fowl, and other exotics like an ibises, parrots, and possibly a flamingo and a female peacocks. That mosaic is pictured below. Above the head of the physical embodiment of magnanimity in the mosaic’s center medallion is a bird with the typical female peacock’s brown coloration and telltale tuft on its head.

One of my earlier blogs remarked on the impact of the coronavirus on our research project and its impact is shown here, too. After eleven years of incorporating the artifacts into the hotel’s construction, the Museum Hotel Antakya opened at the beginning of the pandemic only to have to close. Optimistically, they are taking reservations for June.

The Peacock Cult in Asia by P. Thankappan Nair, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 33, No. 2 (1974), pp. 93-170 retrieved from JSTOR

Thanks to Alex for the enlargement of the Bird Rinceau mosaic.

[1] The Peacock Cult in Asia by P. Thankappan Nair

[2] SmithsonianMag.com, April 20, 2020

Tommpy Tripp